Nicaragua Solidarity Campaign Action Group

11 February 2020

The Nicaraguan deaf children who invented a new language

In the 1980s deaf children in Nicaragua invented a completely new sign language of their own. This remarkable achievement allowed experts a unique insight into how human communication develops.

US linguist Judy Shepard-Kegl documented the emergence of what is now known as Nicaraguan Sign Language.

In this BBC video she explains how the language developed in the context of the inclusive education programmes of the Sandinista Revolution.

The BBC video: The Birth of a New Language

A language has been born before our eyes *

Raise four fingers (the sign for ‘B’), touch your nose with your thumb and dip your hand down to mimic an elephant’s trunk. You’ve just said ‘Babar the Elephant’ in Nicaraguan Sign Language – the sign is distinct from the one for ‘elephant’.

ISN (its initials in Spanish) was developed by children. Until the 1970s, there were no facilities or learning programmes for deaf children in Nicaragua, but with the Sandinista revolution came a new impetus to provide education for kids with special needs. Four hundred deaf children were identified in Managua, and two schools created for them.

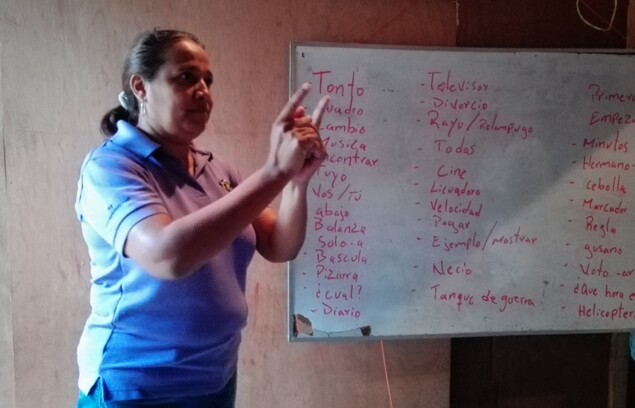

Teachers were brought from Europe who tried to teach Spanish using fingerspelling, which the children couldn’t grasp because they’d never learned Spanish. But they all had their own signs that they used at home. And in the classroom, the playground and the school bus they began to share them, eventually turning impromptu communication into a common language.

I learned about ISN from Kathy Owston, who’s on a three-year career break from St Thomas’s Hospital, working with deaf children in Nicaragua.

A journalist in Estelí called Famnuel Ubeda runs an arts and media project attended by around fifty young people who make a TV magazine show and give news broadcasts for the deaf. He also runs classes in ISN from his mother’s house. Neither project gets government help and he is looking for sponsorship to be able to continue.

Owston has been learning ISN at his class, which runs for three hours on Sunday mornings, attended by 14 primary school teachers and a few parents. One is the mother of Shoskey, the three-year-old who showed Owston how to sign Babar the Elephant.

Brought up in a family with whom he could barely communicate, he now has hearing aids, bought by his parents with substantial help from an overseas donor, and is slowly learning Spanish as well as ISN.

ISN is now an internationally recognised sign language. Judy Kegl, a US sign language expert, established in 1986 that a structured language had emerged. ‘A language has been born before our eyes,’ Steven Pinker wrote in The Language Instinct.

The first ISN dictionary was published in 1996, helping the language to become more widespread, though there isn’t the money for every deaf child to have their own copy.

And it wasn’t until 2004 that interpreters were available, though in the last few years they’ve become more numerous and are seen on TV news channels and at official occasions, notably presidential speeches.

The sign for President Daniel Ortega, who wears a prominent Rolex watch, is tapping your wrist. The late Fidel Castro, often referred to in political speeches, is signed by a bossy wagging of the finger combined with a V-sign moving away from the mouth, as if smoking a cigar.

As new words are needed, new signs emerge. To say ‘Donald Trump’, you make a gesture to indicate a presidential sash then smooth your hair across the forehead.

This article by John Perry was first published in the London Review of Books, July, 2017.

* Steven Pinker, ‘The Language Instinct: How the mind creates language’ https://blindhypnosis.com/the-language-instinct-how-the-mind-creates-language-pdf.html