Nicaragua Solidarity Campaign Action Group

29 February 2024

Rules based international order for the benefit of who?

A reconfiguration of global power is playing out as rage escalates internationally at the refusal of the US, UK and other allies to call for an immediate cease fire in Gaza and to take concrete action to ensure it is implemented by Israel.

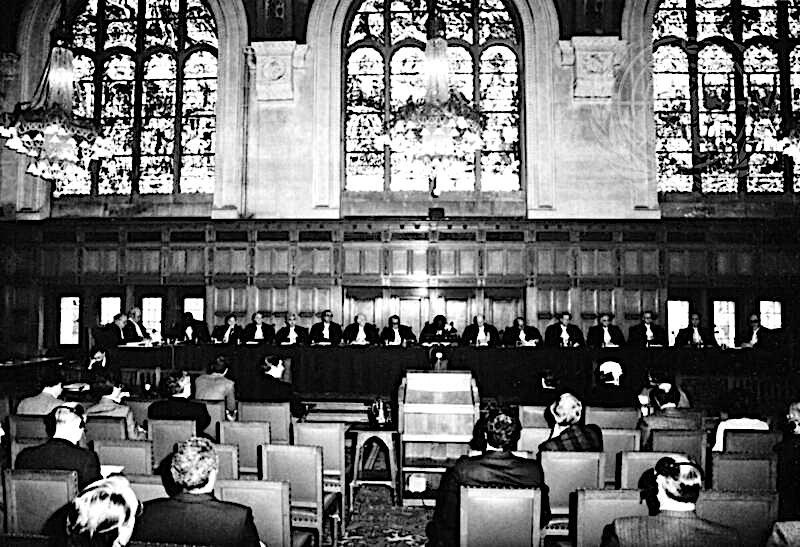

But what is likely to happen if Israel and the US continue to refuse to accept and block the ruling of the International Court of Justice (ICJ)? Will the ruling meet the same fate as that of the ICJ ruling in the case of Nicaragua vs USA of 1986? Or will the reconfiguration of global power in the 1980s assert its influence to ensure a different outcome?

On 26 January 2024 the International Court of Justice (ICJ) announced an interim decision ruling that South Africa’s claims of genocide against Israel are plausible and ordered Israel to “take all measures within its power to prevent the commission of all acts within the scope” of the UN Convention on Genocide. Insert link

The US dismissed the notion that actions of Israel in Gaza constitute genocide. “We continue to believe that allegations of genocide are unfounded,” a State Department spokesperson said.

Israeli lawyer Tal Becker stated that it is regrettable that South Africa ‘put before the court a profoundly distorted factual and legal picture, [and] the entirety of its case hinges on a deliberately curated, decontextualised and manipulative description of the reality of current hostilities”. He went on to accuse South Africa of ‘attempting ‘to weaponise the term genocide.’

If Israel does not comply with the ICJ ruling the issue could go to the UN Security Council where the US has the right to exercise its power of veto. If it does so, the case would go to the UN General Assembly, where no country has veto powers. The result is likely to overwhelming uphold the ICJ ruling, deeply embarrassing for the US and its allies exposing their contempt for international law.

Since the ICJ ruling the UN Security Council has voted for a third time on an Algerian resolution calling for an immediate cease fire. Yet again the resolution was approved with an overwhelming majority of 13 – 1. The US again used its veto powers in defiance of the will of the majority of the world; the UK abstained.

What is likely to happen to the ICJ South Africa vs Israel case? As long as the US causes paralysis in UN institutions by choosing to exercise its power of veto in the Security Council and, along with its allies, continues to provide arms to Israel could this lead to even broader and deeper conflicts? Where are the brakes in the UN system to assert leverage to stop the daily horror in Gaza?

For an example of US contempt for international law and subsequent paralysis of UN institutions, the ICJ case of Nicaragua vs Nicaragua of 1986 is a useful point of reference.

It is no coincidence that Nicaragua has became the first country internationally to officially back the South Africa vs Israel genocide case reflecting not only the country’s ties with Palestine dating back more than 40 years but also Nicaragua’s own experience of pursuing justice through the ICJ against the US to bring an end to the devastation of the 1980s contra war.

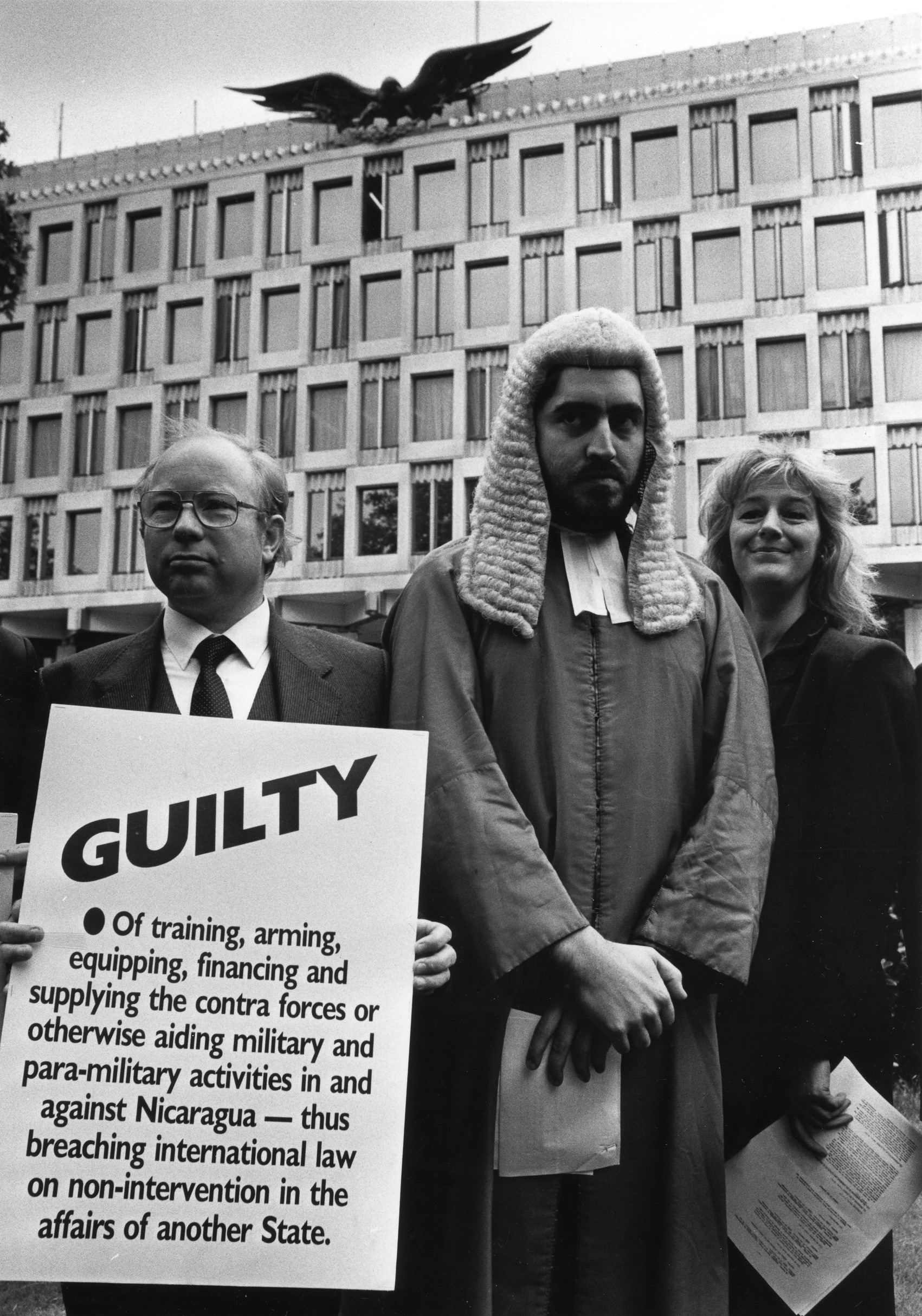

In 1984, Nicaragua brought a case against the US in the ICJ relating to US policies of arming, training and financing a mercenary force known as the contra fighting to overthrow the Nicaraguan government. An additional charge related to the CIA mining of the country’s harbours.

Using a similar argument to Israel’s response to the current ICJ case, the US attempted to justify its policies by claiming it was acting in “collective self-defence”.

Lying some 2,000 miles from the US border, at the time Nicaragua was one of the most impoverished countries in the hemisphere with a population of four million. The court rejected the US ‘justification’ by 12 votes to 3 in its 1986 ruling.

The Court overwhelmingly ruled that the US, “by training, arming, equipping, financing and supplying the contra forces … has acted, against the Republic of Nicaragua, in breach of its obligation under customary international law not to intervene in the affairs of another State.” link to judgement

It determined that the US had been involved in the “unlawful use of force,” with violations through attacks on Nicaraguan facilities and naval vessels, the invasion of Nicaraguan air space, and the training and arming of the contras.

The ICJ also found that President Ronald Reagan had authorised the CIA “to lay mines in Nicaraguan ports” and “that neither before the laying of the mines, nor subsequently, did the US Government issue any public and official warning to international shipping of the existence and location of the mines; and that personnel and material injury was caused by the explosion of the mines.”

The Court ordered the US to cease such activities and later pay reparations of US $17bn submitted by Nicaragua.

The US dismissed the judgment on the grounds that the US must “reserve to ourselves the power to determine whether the Court has jurisdiction over us in a particular case” and what lies “essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of the United States.”

By making such claims, the Reagan administration blatantly revealed that the US considered armed attacks against the sovereign state of Nicaragua fell within its “domestic jurisdiction.”

Nicaragua then took the matter to the UN Security Council where their representative argued that ‘recourse to the ICJ was one of the fundamental means of peaceful solution of disputes established by the UN Charter.’

Nicaragua went on to highlight how essential it was for the Security Council and the international community to remind the US of its obligation to abide by the Court’s ruling and cease its war against Nicaragua.

The US responded that the jurisdiction of the ICJ was a matter of consent and that the US had not consented to the jurisdiction of the ICJ in this case. The US ambassador asserted that US policy towards Nicaragua would be determined solely on the basis of its own national security interests.

Predictably the US continued to refuse to accept the ICJ’s verdict and to this day has not paid $17bn reparations claimed by Nicaragua. Two months later Congress approved a further U$105m funding to continue the war.

By 1990 this had resulted in the deaths of 30,000 people, tens of thousands injured, economic collapse and untold pain and suffering as we now witness daily in Gaza.

In 1986 and again in 1987, Nicaragua turned to the UN General Assembly, which passed resolutions 94-to-3 and 95–2 respectively calling for compliance with the ICJ ruling. It is no coincidence that the two states opposing the resolution were the US and Israel.

The case led to much global criticism by no concrete action internationally due to the power exercised by the US and Israel in paralysing UN institutions.

International lawyer Anthony D’Amato, writing in The American Journal of International Law, argued that “law would collapse if defendants could only be sued when they agreed to be sued, and the proper measurement of that collapse would be not just the drastically diminished number of cases but also the necessary restructuring of a vast system of legal transactions and relations predicated on the availability of courts as a last resort.”

The US, Israel and their allies will be put under intense scrutiny in coming months in respect to compliance with international law.

Will the much changed configuration of global power since 1986 and international outrage at Israel’s war on Palestine be sufficient to outweigh the interests of Israel, the US and its allies?

Or will these interests prevail in a similar way to the 1986 Nicaragua vs USA case that illustrated so graphically that kind of ‘rules based international order’ that the US, UK and their allies constantly champion is lethally and hypocritically restricted to an order that corresponds with their own national interests?